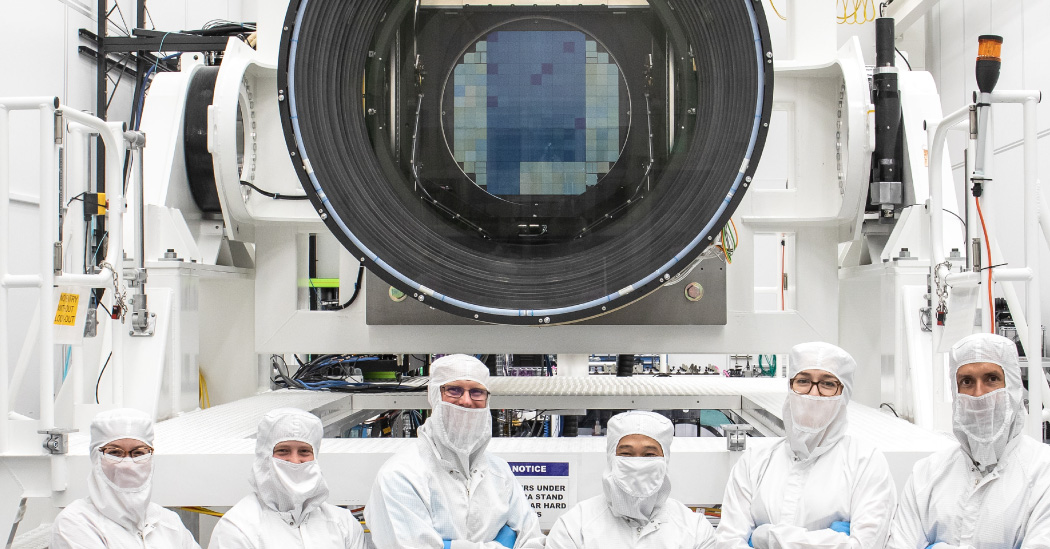

At the heart of the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile is the world’s largest digital camera. About the size of a small car, it will create an unparalleled map of the night sky.

The observatory’s first public images of the sky are expected to be released on June 23. Here’s how its camera works.

When Times reporters visited the observatory on top of an 8,800-foot-high mountain in May, the telescope was undergoing calibration to measure minute differences in the sensitivity of the camera’s pixels. The camera is expected to have a life of more than 10 years.

A single Rubin image contains roughly as much data as all the words that The New York Times has published since 1851. The observatory will produce about 20 terabytes of data every night, which will be transferred and processed at facilities in California, France and Britain.

Specialized software will compare each new image with a template assembled from previous data, revealing changes in brightness or position in the sky. The observatory is expected to detect up to 10 million changes every night.

Some changes will be artificial. Simulations suggest that roughly one in 10 Rubin images will contain at least one bright streak or glint from the thousands of SpaceX Starlink and other satellites orbiting Earth.

Despite streaks, clouds, maintenance and other interruptions over the next decade, the Rubin Observatory is expected to catalog 20 billion galaxies and 17 billion stars across the Southern sky.